FOREWORD

DR. AVI FRIEDMAN

The design of Canadian homes has undergone a remarkable transformation in recent decades. Owing primarily to a cohort of talented architects, a unique residential design identity has been established. In a country as vast as Canada, the second largest land mass in the world, one needs to recognize that regional differences are expected and do exist. Yet, there are similarities between the conditions that the designers of many of the featured projects in this book faced, all rooted in the nature of place.

If one is to survey the geographical make-up of Canada, most provinces can boast large swaths of forested land and ample bodies of water, be they lakes or oceans.The designers of the rural homes creatively embed them in their natural surroundings. In fact, it seems that a view to the distance has been a prime conceptual consideration. Turning the living areas toward a lake or forest and in some cases both was a principal idea underlining the design of most of the homes. To benefit from the breathtaking views, some designs include large glazed façades as if to bring the outside in. Moreover, many of the homes have been placed very close to trees to make them appear part of the forest or to use the trees as a natural shading device in summer time.

Orientation has also played a pivotal role in responding to recent environmental challenges faced by us all. The openings are south facing for passive solar gain, contributing to a reduction in the use of energy-consuming means of costly mechanical heating.

Even in a cold country like Canada where the temperature hovers well below zero, there are ample sunny days in wintertime. In addition, the cross ventilation in many of the designs will create natural cooling, reducing the need for air conditioning. Being a northern country with few winter daylight hours means that enjoying them is a priority. As a result, the inclusion of skylights to light darker areas such as hallways and bathrooms is another notable design strategy. The additional natural light is complimented by the use of white walls from which it is reflected.

The innovative use of building materials is another common feature that runs through the design of the homes. The chief building material of low-rise Canadian buildings is lumber. Recent technological development sees the use of wood in the construction of taller buildings as well. The species most used fall under two main categories: softwood—spruce, pine, and cedar; and hardwood—maple and oak. The use of these species is creatively embedded in the exterior and the interior of the homes featured. Internally, the use of wood for flooring, stairs, and even built-in furniture, is highly noticeable. The wood has been varnished to accentuate the material’s natural beauty and expose its grain. In some homes, in addition to visual appeal, it adds a measure of warmth and domesticity to the designs. In others, it suitably contrasts with white walls or dark kitchens.

Broadly speaking, the residences can be grouped in two categories: rural and urban. The designers of all the homes considered, of course, the site’s context while crafting the design. For some, the context implied paying particular attention to the natural surroundings, while others respected the rural architectural vernacular, which they layered with contemporary interpretation. Alternatively, the designers of the urban homes have chosen to ignore the characteristics of the neighbouring homes to introduce new design alternatives that are likely to pave the way to the transformation of the entire neighbourhood. The urban homes are cladded, with masonry clay brick chief among them.

More transformations are expected in the coming years in the Canadian residential landscape. Responding to environmental challenges, considering new demographic groups, and introducing innovative building technologies and materials are expected to give rise to new design ideas. If the projects featured in this volume are a mark of things to come, the design of Canadian homes will continue to evolve.

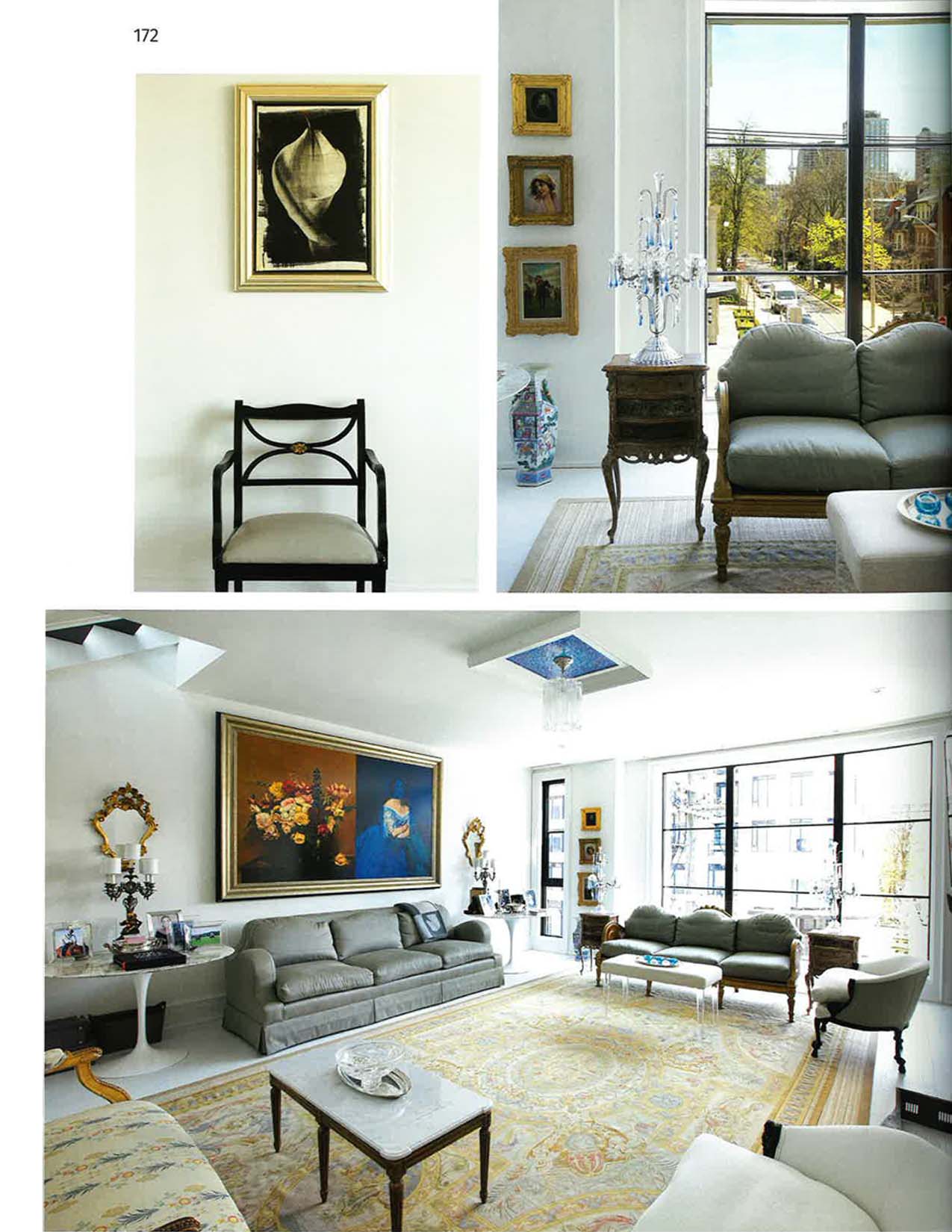

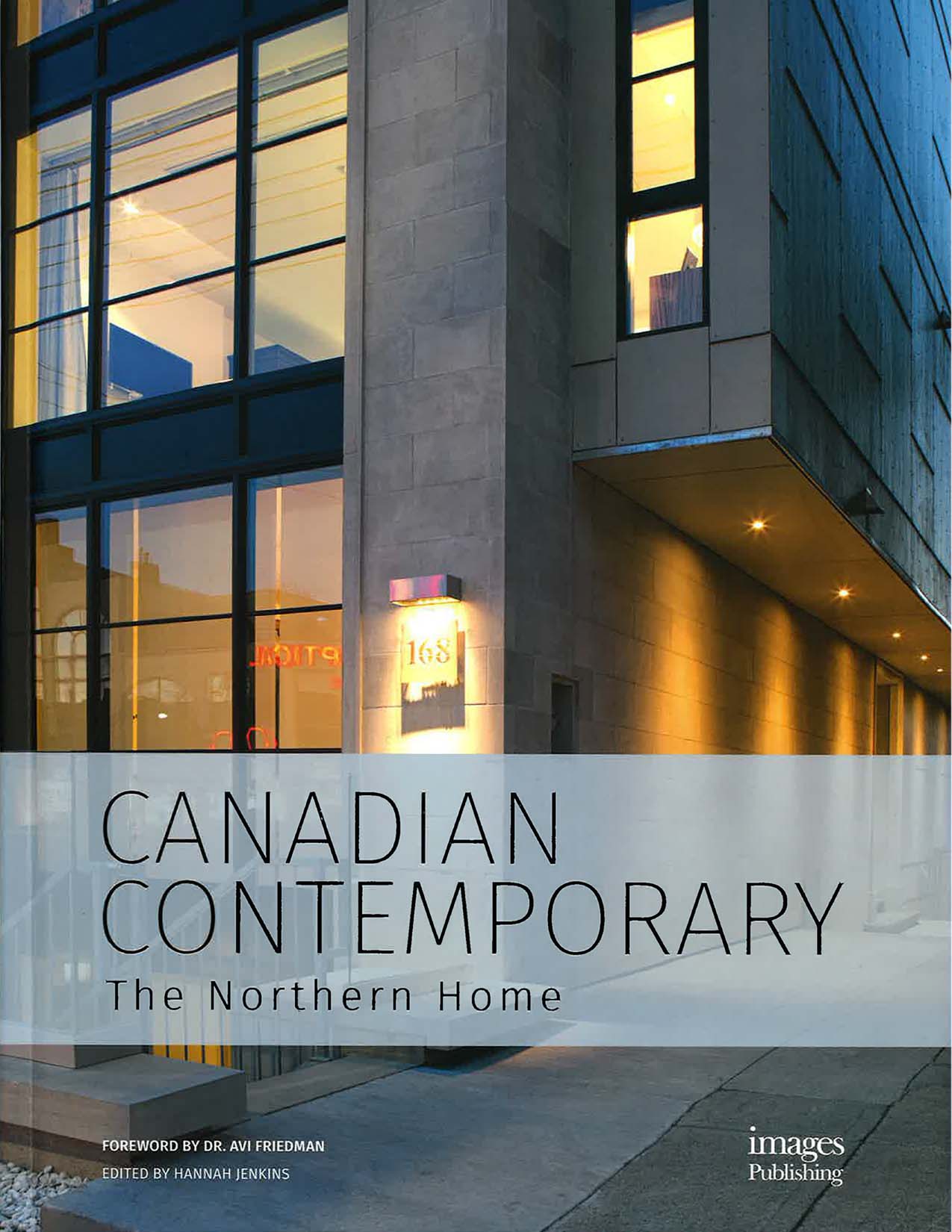

While living in New York City the architect designed and built this Toronto brownstone with the intent of bringing a touch of Upper East Side flair to Yorkville. The front facade is Indiana limestone with black curtain-wall windows detailed by frameless glass railings at the edge of the roof garden. On a street dotted with art galleries, the residence is entered along the side via limestone and granite stairs. The 6639-square-foot (617-square-metre) home spans six levels and exudes classic modern style.

The main level comprises a formal dining space, gallery, family room, kitchen, and mahogany barbeque terrace. The second level includes two bedrooms with en suite and a family room. The third level has been designed for formal living, with a baby grand piano and master-bedroom suite leading out to a rooftop garden. The mahogany decked rooftop enjoys 360-degree city views, a fire pit, gas heaters, and an awning to cover the outdoor dining space when necessary. Inside, the window of the mechanical penthouse, which floats above the roof garden, frames a chandelier located above an open-riser stair.

At the home’s lowest level is a live/work office with six workstations and street access through a 170-square-foot (16-square-metre) limestone light well. Down the hall on the same level is a library and access to four car spaces, two indoor and two outdoor, with concrete heated floors. Externally the home presents a traditional four-storey limestone facade, while stepped cement panel cladding with metal flashing and a cantilevered column over the main floor give it a modern edge. This Toronto brownstone is an architectural blend of past and present that compliments the way residents live and work in the current day.